Escaping the Build Trap: How Effective Product Management Creates Real Value

Written by Melissa Perri, Escaping the Build Trap: How Effective Product Management Creates Real Value essentially re-architects the software development lifecycle by anchoring it on actionable feedback from the customer. Actually, we probably shouldn’t write a single line of code before we are sure the customer needs the feature. Even then, you provide a minimal feature set (MVP) in alpha state and validate their effectiveness. Collecting feedback at the “tail end” of the flow is an important step, as it closes the loop and orients development of the product in a focused way that provides confidence on its value proposition.

Written by Melissa Perri, Escaping the Build Trap: How Effective Product Management Creates Real Value essentially re-architects the software development lifecycle by anchoring it on actionable feedback from the customer. Actually, we probably shouldn’t write a single line of code before we are sure the customer needs the feature. Even then, you provide a minimal feature set (MVP) in alpha state and validate their effectiveness. Collecting feedback at the “tail end” of the flow is an important step, as it closes the loop and orients development of the product in a focused way that provides confidence on its value proposition.

Check out some other books I’ve read on the bookshelf.

Summary

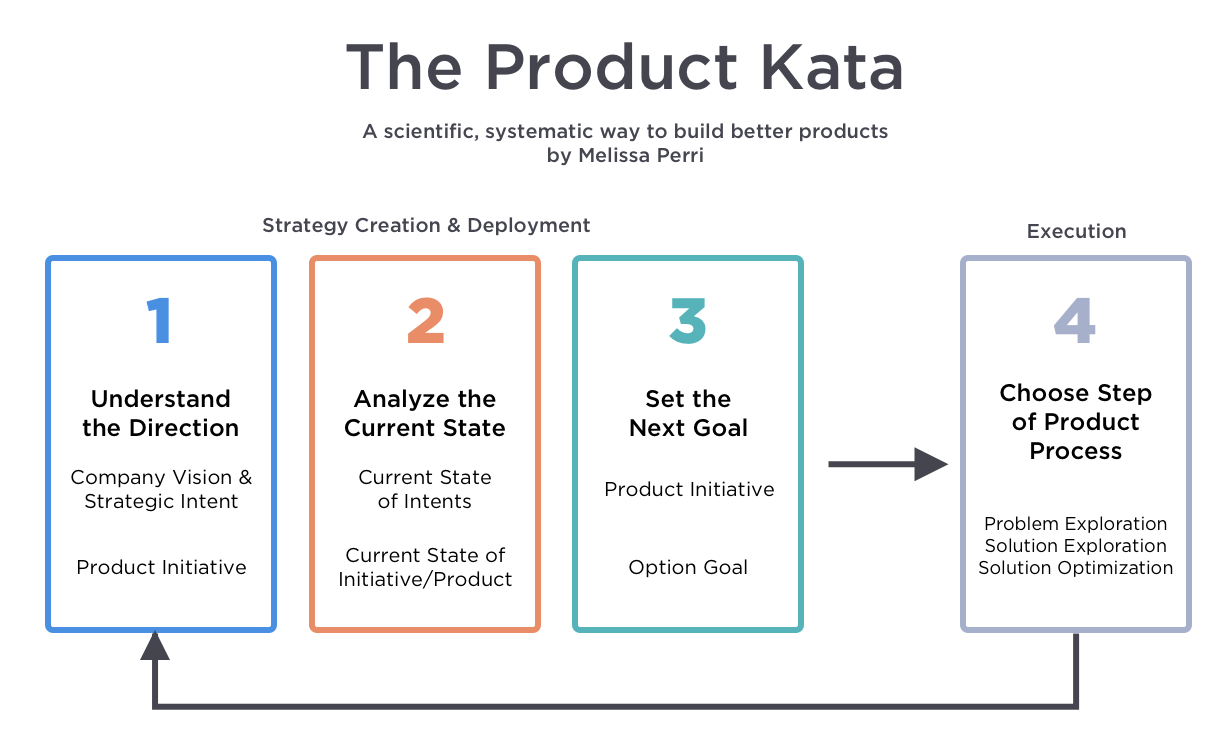

Escaping the Build Trap criticizes the tendency of many companies to measure their success by the number of features shipped rather than the value those features create for their customers and how that value helps further the company’s strategic objectives. The term product-led is coined to describe an alternative process that begins with identifying the strategic objectives and the value proposition for the customer base that would result in furthering those objectives. This process is embodied in the Product Kata and borrows from the scientific process by redefining the organization’s approach to problem-solving to be one of experimentation and testing of hypothesis. A hypothesis is tested in small incremental steps as fast as possible, with bad ideas discarded while good ideas that provide value are kept.

For me, as a software engineer, this book reaffirms my commitment to in general focus on the things that really matter - things that provide actual value - and defer or discard the rest.

What is the Build Trap?

The build trap is when organizations become stuck measuring their success by outputs rather than outcomes. It’s when they focus more on shipping and developing features rather than the actual value those things produce.

Part I, The Build Trap

What we know and what we don’t

When figuring out what product or feature to build we must first figure out what we know and don’t know:

| Known | Unknown | |

| Known | Facts | Questions |

| Unknown | Intuition | Discovery |

Chapter 5: What We Know and What We Don’t

- Known-knowns: facts gathered from data or critical requirements (regulations or basic needs for the job).

- Known-unknowns: clarified enough that you know which questions to ask

- Unknown-knowns: Here Be Dragons. This is where bias thrives. Known-unknowns are born out of years of experience and are based on intuition.

- Unknown-unknowns: the things you don’t know that you don’t know. You don’t know enough to ask the right questions or identify the knowledge gaps. These are moments of surprise that need to be discovered as you sift through unrelated data or talk to customers.

How does this fit into the Agile process?

Agile […] promote[s] a better way of collaboration and a faster method of building software, but it largely ignores how to do effective product management.

Agile assumed that someone was doing that front-of-funnel part, generating and validating ideas, and instead optimized the production of software. Yet, that piece has been lost along the way, as companies believe that Agile is all you need to do successful software development. So, many product managers in Agile organizations still operate with this Waterfall mindset.

Chapter 6: Bad Product Manager Archetypes

This is a fascinating distinction; it had never occurred to me that while doing “agile” we were still stuck in this waterfall mindset!

Speaking of validating ideas…

The Product Death Cycle

The Product Death Cycle is likely to occur when we end up with a mindset geared towards reactive thinking as opposed to strategic thinking, when we are implementing ideas without validating them:

The Product Manager

What does a great Product Manager look like?

Chapter 7 A Great Product Manager does into some depth - I’ve summarised the contents in the following paragraphs.

The term “Product manager” is misleading - the role is not a manager in the traditional sense of the word. The role does not come with much direct authority. Product Managers are effective when working through others, recognizing their strengths, in order to achieve their common goal.

Product managers know why the team is building what they are building. Armed with this why they can convince the team that this is the right direction to go in.

To figure out the why or what to build takes a strategic and experimental approach. Product Managers take input from customer research, expert information, market research, business direction, experiment results, and data analysis, using those inputs to craft a vision for the product that will solve the customer’s needs and further the company’s vision.

Since the Product Manager has to wear many hats, they need to be able to speak both the business language and the technical language to certain degrees. They don’t need to be experts in either, but should be sufficiently versed in both domains so that they can discuss tradeoffs with teams on both domains.

A product manager must be tech literate, not tech fluent.

Chapter 7: A Great Product Manager, section Tech Expert Versus Market Expert

A Great Product Manager starts with Why. These why questions are productive and purposeful:

- How do we determine value?

- How do we measure the success of our products in the market?

- How do we make sure we are building the right thing?

- How do we price and package our product?

- How do we bring our product to market?

- What makes sense to build versus buy?

- How can we integrate with third-party software to enter new markets?

What does a bad Product Manager look like?

- The Mini-CEO

- arises out of the myth that the role has sole authority over the product.

- The Waiter

- the product manager who is at heart an order-taker. They ask stakeholders for what they want and turn all those wishes into an itemized list of features. There is no vision. There is no decision-making involved. And because they have to goals in which to provide context for tradeoffs, the priority of these features becomes a popularity contest for whomever is making the request.

- The Former Project Manager

- more focused on the when instead of the why.

The Product-Led Organization

The product-led organization is characterized by a culture that understands and organizes around outcomes over outputs, including a company cadence that revolves around evaluating its strategy in accordance to meeting outcomes. In product-led organizations, people are rewarded for learning and achieving goals. Management encourages teams to get close to their customers, and product management is seen as a critical function that furthers the business.

Part V: The Product-Led Organization

Outcome-Focused Communication

In a product-led organization the communication during meetings tends to become more focused on outcomes. Example from the book:

At the next quarterly business review, Karen was able to speak about the accomplishments of the team.

“This quarter, we were able to launch the video-editing software and onboard 150 new classes to our site, all in key areas of interest for our users. Since the launch of those courses, we have seen an increase in acquisition rate from 15% to 25%, and our retention numbers have risen to 60%. We’re well on our way to reaching our goals. With the additional efforts from other teams around this strategic intent, we’ll hit our goal early - within a year and a half.”

Chapter 20: Outcome-Focused Communication

To note in this example:

- absolute numeric quantities are provided to give a sense of the scale of adoption

- “key areas of interest” reminds everyone that the effort is focused on priorities

- relative numeric figures are provided to compare before-after, and, when combined with the timeframe (a quarter), it gives a sense of the velocity of change and sets up expectations

- ends with a deadline of a year and a half, meaning it has a clearly defined goal and end-date

Roadmaps

Do not think “gantt chart”!

Think of roadmaps as living documents, as an explanation of strategy and the current stage of your product.

A few key parts:

- The theme

- The Hypothesis

- Goals and success metrics

- Stage of development

- Any important milestones

Useful terminology for phases of a feature:

- Experiment

- No production code is being created. The team is understanding the problem and determining whether it is worth solving.

- Alpha

- The team is determining whether the solution is desirable to the customer with a minimum feature set with production code for a small set of users. The users understand they are getting early access to a feature that might change or be killed.

- Beta

- The team is determining whether the solution is technically scalable. This release is available to more customers than the Alpha phase.

- Generally Available (GA)

- The solution is widely available to all customers and the sales teams can talk openly about GA products and features.

A Good Strategic Framework

A good strategy is not a plan; it is a framework that helps you make decisions.

Part III: Strategy

Creating a Strategy

Chapter 12: Creating a Good Strategic Framework, Figure 12-3

Chapter 12: Creating a Good Strategic Framework, Figure 12-3

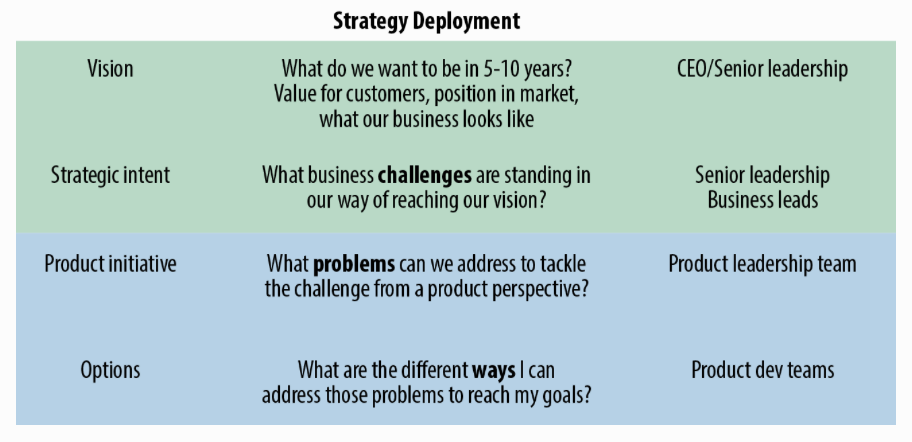

Deploying a Strategy

Chapter 12: Creating a Good Strategic Framework, Figure 12-1

Chapter 12: Creating a Good Strategic Framework, Figure 12-1

The rows in green are deployed at the company level, the rows in blue are deployed at the individual product level.

Rewards and Incentives

Do not tie bonuses and promotions to how many features were shipped, rather incentivize for learning and problem-solving for customers.

Safety and Learning (culture)

To properly deploy adequate and product-led rewards and incentives the company’s culture must provide enough safety to fail and learn. Big asterisks mark big caveats here:

This doesn’t mean that we should be failing in spectacular ways. With the rise of Lean Startup, we began to focus on outcomes, yes, but we also started to celebrate failure. I want to be clear here: it is not a success if you fail and do not learn. Learning should be at the core of every product-led organization. It should be what drives us as an organization.

It is just better to fail in smaller ways, earlier, and to learn what will succeed, rather than spending all the time and money failing in a publicly large way.

Chapter 22: Safety and Learning